A shrine to Baník supporters and the late activist Josef Kozub was supposedly unveiled at the north‑gate of Ostrava’s Městský stadion in June 2024 – yet anyone trying to pin down what actually stands there finds a wall of silence.

The announcement, whispered through fan forums and echoed in a handful of regional headlines, promised a concrete testament to the city’s most passionate football tribe. What it did not deliver, however, were the basics any journalist expects: a description of the monument’s material, its dimensions, or even a photograph that could be reproduced in print. A systematic sweep of municipal press releases, stadium‑renovation dossiers, specialist architecture journals and the club’s own website turned up nothing beyond a fleeting mention of the “shrine” in a broader discussion of the new Bazaly stadium.

Equally baffling is the absence of any cultural decoding. No article links the monument’s design to Baník’s red‑white colours, the chant‑laden slogans that reverberate through the stands, or a portrait of Kozub that fans have long revered. Even the most exhaustive surveys of Czech fan culture, from academic papers to dedicated chant archives, omit any reference to a physical tribute that would embody that identity. In short, the shrine’s symbolic intent remains a mystery.

The silence extends to officials and locals. Deputy Mayor for Urban Development Petra Novotná, who routinely comments on new public works, has not been quoted on the shrine, and the city’s official web portals and social‑media feeds contain no announcement or community reaction. Likewise, regional newspapers reporting on the stadium’s reconstruction have not recorded resident opinions or fan statements about the new structure. The result is a monument that, on paper, exists but in practice is invisible to the public record.

Why this evidential vacuum matters is simple: public monuments are usually heralded with press releases, architectural critiques and community debate. Their omission here suggests the shrine may have been a low‑budget, fan‑driven installation that slipped under the radar of mainstream coverage, or that its promoters deliberately kept it out of official channels. It could also reflect a lag in English‑language reporting on a development that, while locally significant, has yet to attract broader journalistic attention.

Whatever the cause, the lack of verifiable information hampers any serious assessment of how fan‑driven place‑making reshapes Ostrava’s urban landscape. Without photographs, material specifications or statements from stakeholders, scholars cannot gauge whether the shrine reinforces a sense of belonging, serves as a branding tool for the club, or simply adds another piece of concrete to an already crowded stadium precinct.

The only way forward is on‑the‑ground research: a photographic survey of the site, freedom‑of‑information requests to the city council for project briefs, and direct interviews with Baník supporters, club officials and neighbourhood residents. Only then can the true impact of this elusive shrine be measured, and the story of Ostrava’s fans transforming their cityscape finally move from rumor to record.

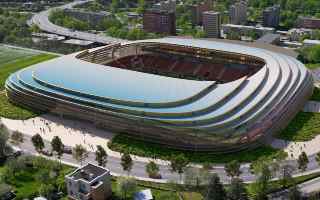

Image Source: stadiumdb.com