Kazakhstan is betting big on a new silicon‑alloy hub in Karaganda, touting it as the answer to Europe’s hunger for home‑grown critical materials and a hedge against Asian supply shocks. Yet the glittering ambition masks a stark reality: the flagship plant’s output figures remain a mystery, and its environmental credentials are barely sketched on a page.

The only concrete capacity number on the table comes from a sister project in Ekibastuz, where Mineral Product International will crank out 80,000 tonnes of ferrosilicon a year – a respectable benchmark, but one that serves a different market to the high‑purity silicon Europe needs for semiconductors and solar cells. In Karaganda, officials describe the existing metallurgical‑silicon output as “insignificant” and refuse to disclose any target tonnage for the planned cluster, leaving analysts unable to gauge whether the venture can truly displace Asian imports.

Financing is equally one‑sided. The Development Bank of Kazakhstan has earmarked up to 2.6 trillion tenge for the groundwork of metallurgical clusters, part of a wider 6.9 trillion‑tenge package covering 14 projects. Meanwhile, the Bank for Development of Kazakhstan has rolled out a US$1 billion credit line for rare‑material projects between 2025 and 2030, with loans as low as US$9.4 million and ten‑year maturities that could be tapped for the silicon hub. What is conspicuously absent are any disclosed foreign investors or private‑sector partners – a gap that raises questions about risk sharing and the infusion of international expertise.

Energy demand is another blind spot. The Karaganda plan includes a dedicated power infrastructure to meet the “high electricity demand of high‑purity silicon production”, but no details emerge on the fuel mix, renewable share or carbon‑intensity targets. Across all the documentation, there is no mention of green‑hydrogen, carbon capture, emissions caps or alignment with the EU’s Green Deal. In a market where European buyers now demand verifiable low‑carbon footprints, the lack of a clear sustainability roadmap could become a deal‑breaker.

European industry analysts are watching keenly. They argue that without transparent emissions data and third‑party certifications, Kazakh silicon will struggle to win contracts that are increasingly tied to EU green‑procurement rules. The silence on green‑finance instruments – no green bonds, sustainability‑linked loans or inclusion in the AIFC Sustainable Finance Centre’s portfolio – further undercuts the cluster’s credibility in the eyes of climate‑conscious buyers.

To move from rhetoric to reality, Kazakh authorities must publish a detailed production timetable for Karaganda, complete with annual tonnage targets and ramp‑up phases. They should also secure and disclose green‑finance backing, outlining renewable‑energy sourcing percentages, carbon‑capture plans and compliance with EU sustainability standards. Such transparency would not only attract the private and foreign capital that is currently missing but also reassure European customers that Kazakh silicon can meet both technical and environmental criteria.

If Kazakhstan can fill these information gaps, the silicon‑alloy cluster could become a linchpin in a more resilient, diversified supply chain for Europe’s high‑tech and renewable‑energy ambitions. Until then, the project remains a high‑profile promise on paper, with its true capacity and climate credentials still hidden behind state‑driven funding and a veil of ambiguity.

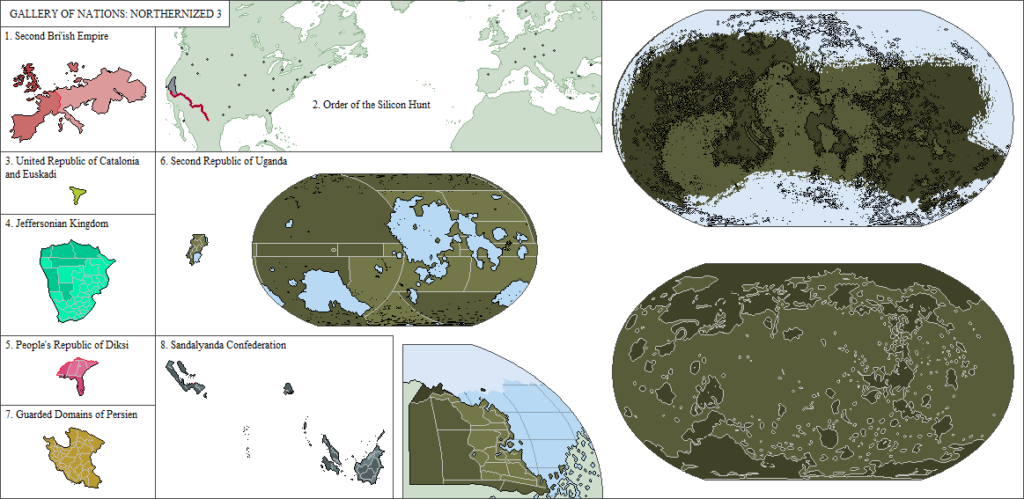

Image Source: www.deviantart.com