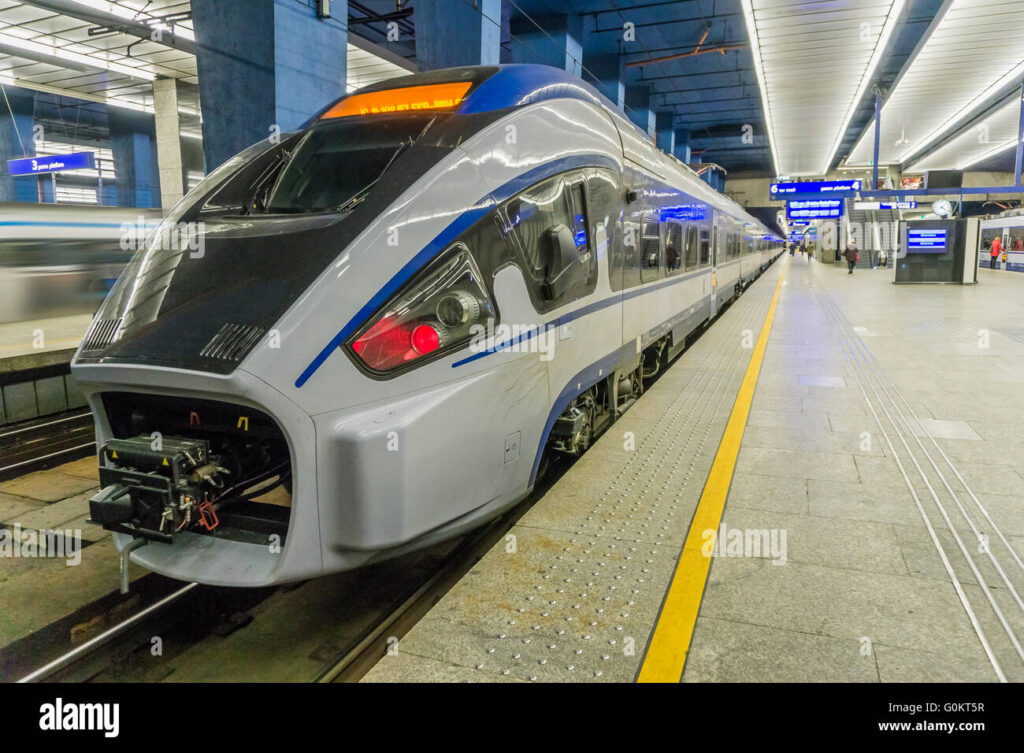

Four brand‑new Stadler FLIRT electric multiple units rolled out in Warsaw this week, marking the latest thrust in a long‑overdue modernisation of Poland’s regional rail. The delivery lifts the operator Koleje Mazowieckie’s FLIRT fleet to 64 trains and underlines a €‑heavy European‑funded push to stitch together Central Europe’s transport corridors. Yet, while the sleek five‑car sets promise higher capacity and speed, the promised minutes shaved off journeys and the economic windfall for border regions remain frustratingly unquantified.

The Warsaw‑specification FLIRT is a five‑car, 600‑passenger machine (279 seats) capable of 160 km/h on the open line. Continuous power sits between 660 kW and 1 000 kW, with peaks up to 1 750 kW, and acceleration can reach 1.3 m/s² – enough to bolt out of stations faster than the ageing stock it replaces. Low‑floor entry ranging from 550 mm to 1 200 mm guarantees level boarding for all users, while multi‑system electrification compatibility (25 kV AC, 15 kV AC, 1 500 V DC, 3 000 V DC) future‑proofs the units for cross‑border services toward Belarus and Lithuania.

In theory, those figures translate into shorter dwell times and the ability to run more frequent services on the Warsaw‑Kraków axis and the north‑eastern links to Białystok, Grodno and Vilnius. The 18‑year maintenance contract tied to the European Funds for Mazovia 2021‑2027 programme should keep the fleet reliable enough to support higher frequencies, a crucial step for corridors that double as freight arteries. However, the railway operator and infrastructure manager PKP PLK have yet to publish any concrete timetable revisions for the three flagship routes.

The winter‑timetable announcement listed modest gains on unrelated lines – three minutes on Warsaw‑Szczecin and eight on Olsztyn‑Poznań – but omitted any figures for Warsaw‑Kraków, Warsaw‑Białystok‑Grodno or Warsaw‑Białystok‑Vilnius. Attempts to extract baseline journey times from major travel‑planning portals were thwarted by 403‑forbidden errors, leaving analysts without the before‑and‑after data needed to verify any speed‑up claims. As a result, any assertions about saved minutes remain speculative, despite the FLIRT’s superior acceleration and higher top speed.

Equally opaque is the economic impact picture. No public forecasts link the new rolling stock or the associated line upgrades to GDP growth, trade volume, or job creation in Poland’s Podlaskie Voivodeship, Belarus’ Grodno oblast, or Lithuania’s Aukštaitija region. Regional overviews merely note that Grodno’s gross regional product lags its targets, while Podlaskie and Aukštaitija receive no quantifiable uplift figures at all. Nonetheless, positioning the FLIRT fleet on TEN‑T corridors – the EU’s trans‑European transport network – should, in principle, improve passenger mobility, bolster freight throughput and stimulate tourism, all classic levers of regional prosperity.

The stark data gap underscores a broader transparency problem. Without publicly accessible timetables and dedicated impact studies, policymakers, investors and the media are left to gamble on optimistic projections. EU TEN‑T methodology offers a ready‑made modelling framework, but it has yet to be applied to the specific Podlaskie‑Grodno‑Aukštaitija corridor.

To move beyond hype, transport authorities must commission baseline‑and‑post‑implementation analyses that spell out exact minutes saved and feed those results into regional economic models. Opening timetable data on travel‑planning platforms would enable independent verification, while a continuous monitoring system for punctuality, load factors and passenger satisfaction would provide the hard evidence needed to justify further investment. Until then, the FLIRT’s sleek silhouette remains a promise rather than a proven driver of faster cross‑border journeys and tangible economic gains.

Image Source: www.alamy.com